by Mary Anne Duggan

As a dutiful kindergarten teacher, I always wrote my lesson plans a week in advance. It just so happened on the schedule for September 11, 2001 was a class book the students would create entitled What a Wonderful World. The plan was to play a recording of Louis Armstrong’s song of the same name while the students each illustrated a sentence from the song.

I see trees of green

Red roses, too

I see them bloom for me and you

And I think to myself, what a wonderful world

This on a decidedly not-wonderful morning. Just a few hours prior I woke my husband from his post-night shift slumber to let him know he would be putting on his uniform again. I wrenched with whether I should drop off my daughter at middle school. Were we all in danger? Would school even be held? I dropped her off and brought my son to our school not knowing what would happen next.

In the faculty room before the first bell, we deliberated on how much to discuss with the students. In that moment, the kindergarten team decided to treat it like a normal day and gently answer any questions as they arise. (And cross fingers that they would not!)

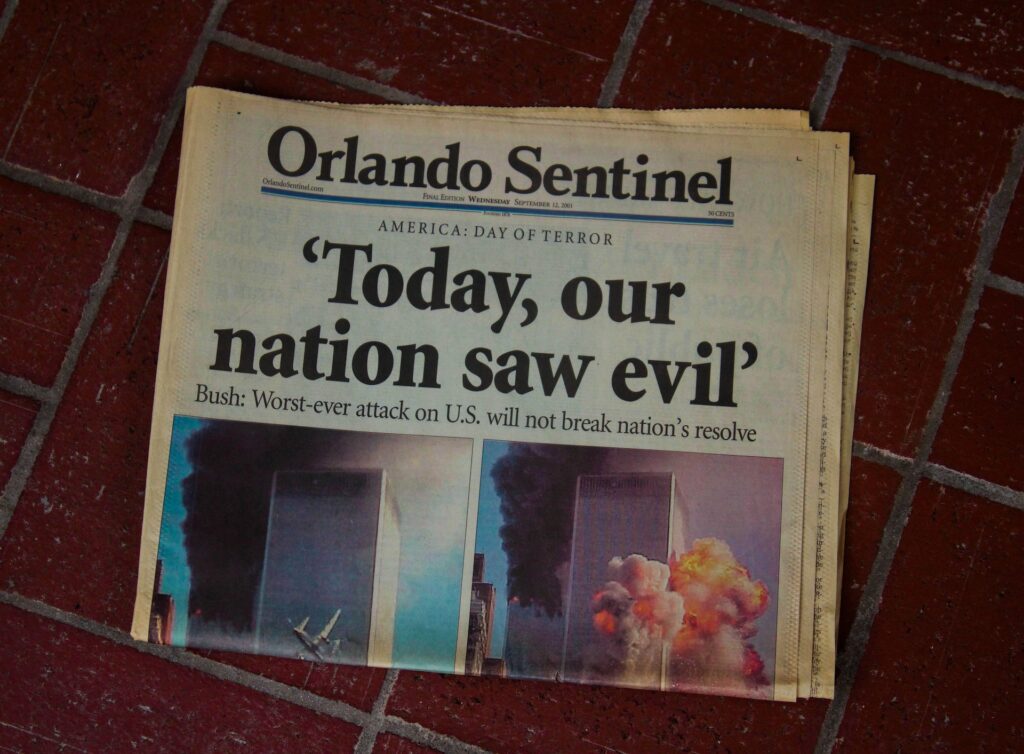

Fast forward to Armstrong’s powerful voice playing in my classroom later that morning and me trying to stuff down the tears of the moment. Up to that point, no student had said a thing about the terrorist attack, except for Matthew who came running up to me at the start of the day. “Some planes flew into the Twin Towers!” he shared with me in his strong, 5-year old New York accent.

As the students each illustrated their page of the book, (a book I still have over 20 years later), pictures of blue skies and rainbows and people really saying I love you filled their pages. But Matthew made a different artistic choice. On his page was an airplane with two rising towers in its sights.

I learned then what I continue to believe now. Current events let themselves into our classrooms unbidden. And even if only some of my students are aware of them, as the teacher I, too, am affected. The question for me, then, is not if current events should be part of classroom dialogue, but how.

Acknowledging contagious ideas

On a brisk February day 18 years after 9/11, I again stood in front of a class – this time a college statistics class. I was trying to teach about z-scores that day, but the students were more interested in talking about this weird new virus that was going around. I remember one nursing student saying to the whole class, “Hold on, people – It’s coming!”

If I taught social psychology, we could have discussed the phenomenon of conspiracy theories or the sway of confirmation bias. If I was a nursing instructor, we could have focused on hand-washing and other ways to prevent germ spread. I could have espoused theories about how a pandemic should be handled, but I don’t teach public health. I could have gone all sorts of political, but I resisted.

Since I teach statistics, however, there was plenty to tie in. We talked about probabilities associated with the virus and base-rate errors people are inclined to make. We learned how to calculate rates of contagion and R-naught ratios. We talked about how COVID deaths were operationally defined from a statistical perspective– a sad discussion but one the students really wanted to have. In short, we kept to the content of statistics, and that gave us plenty to chew over. And, I believe in neutrally approaching this topic and sticking to the science, students gained some knowledge that may have helped them find their footing when it seemed the floor was dropping out from under them.

Current events run in the news on a loop and some students walk into our classrooms replaying that loop in their minds. Current events can either serve as a massive distraction for students or as a vehicle for powerful learning. I choose to minimize the former by capitalizing on the latter.