A popular book proclaimed that everything we need to know we learned in kindergarten. For me, everything I needed to grow into a healthy human I learned as a teacher of Introduction to Psychology. I don’t think I’m overselling it – teaching this course has changed the trajectory of my life.

The story is not a pretty one. Rather, mine was a story of do as I teach, not as I do. The prescription for physical and mental wellness is woven throughout any PSY 101 textbook, and I was doing my best to dole out the appropriate medicine to my students.

“Adequate sleep helps memory consolidation.”

“There is a link between exercise and a positive mood.”

“Stress can be regulated through mindfulness and meditation.”

Meanwhile, I myself was sleeping too little, sitting too much, and stress dominated most of my days. I regularly used food to regulate my mood. How I could warn my students about the “self-medication hypothesis” with a straight face remains a mystery to me.

But, with each new group of students, my awareness of my own hypocrisy grew. Just as I was beginning to muse about making some healthy changes, life hurried me along. Faced at the time with a more pressing need to find balance in my life, I turned to lessons ripped from the pages of PSY 101. I wanted to achieve greater peace in my life and get down to a healthy weight. I wanted more energy to face life’s challenges. I wanted strength when I was feeling broken.

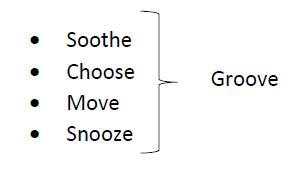

As an educational psychologist, I know a little bit about how change happens. I know simplicity can be key when forming new habits, and I also know the power of mnemonic devices that help us to remember our goals. I therefore focused on just the following five directives from psychological research on how to live a healthy life (and they just so happen to rhyme!):

Soothe involves finding ways to regulate stress. Choose means opting, for the most part, to eat foods that make the body feel good and provide energy. Move involves finding some way to engage the body every day, even if it is just a walk around the block. Snooze means taking sleep hygiene seriously and getting in those zzz’s. Groove underpins all the previous elements and relates to setting up structures and habits that lead to healthy actions (like planning workouts for the week and stocking the fridge with veggies).

There is nothing sexy about this prescription. It also is no quick fix. There is nothing extreme involved, but rather balance is at the centerpoint. Each day I remember the words soothe, choose, move, snooze, and groove, and they help me to stay in balance.

So what did these five words do for me? Over a year later, I am perhaps healthier than I have ever been in my life. I have a much deeper sense of inner peace. I went from a BMI classified as “obese” to one smack-dab in the “normal” level. I feel energetic and strong. And, I no longer feel like a phony when sharing with my students how to be healthy and well.

This post is part of the Write 6X6 challenge at Glendale Community College.

The post How Teaching Psych 101 Saved My Life (or at least made it a lot better!) appeared first on My Love of Learning.